Article 26: Right to Education

UDHR Article 26

1. Everyone has the right to education. Education shall be free, at least in the

elementary and fundamental stages. Elementary education shall be

compulsory. Technical and professional education shall be made

generally available and higher education shall be equally accessible to all

on the basis of merit.

2. Education shall be directed to the full development of the human

personality and to the strengthening of respect for human rights and

fundamental freedoms. It shall promote understanding, tolerance and

friendship among all nations, racial or religious groups, and shall further

the activities of the United Nations for the maintenance of peace.

3. Parents have a prior right to choose the kind of education that shall be

given to their children.

In 2002, when the Kenyan government announced free primary school education for all, Kimani Ng’ang’a Maruge decided to enroll in Grade One. What’s unusual about that? He was an 84-year-old great-grandfather. A photo on the front page of a Kenyan newspaper showed him sitting at a tiny desk next to six-year-olds, wearing a uniform he had fashioned for himself, complete with regulation shorts.

Maruge said he wanted to learn to read the Bible to find out if preachers had been quoting it correctly all his life. He lived five more years, was certified by the Guinness Book of World Records as the oldest person to enroll in primary school, and was taken to New York to address the UN Millennium Development Summit on the importance of free primary education.

“Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.”

–Nelson Mandela

Article 26 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) makes universal free primary education compulsory, and is usually thought of as a right about children. But as Maruge showed, people of any age can seek and benefit from education and literacy. Not only was a movie made about his life, but his story inspired many dropouts in Kenya to return to school and complete their education.

This right is further enshrined in various international conventions, in particular the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (which has been ratified by every country except the United States). In Article 26 of the UDHR, we see the right to “full development of the human personality,” which also appears in Articles 22 and 29. It is clear the drafters saw this term as a way of summarizing many of the social, economic and cultural rights in the Declaration, and there has been an increasing focus by international bodies on the role of education in empowering individuals – both children and adults.

Unusually for the UDHR’s long list of rights, this one has in some respects been widely achieved. More children around the world have access to education today than ever before, with rates of primary school attendance for girls rising to parity with boys in some regions. The overall number of children out of school worldwide declined from 100 million in 2000 to an estimated 57 million in 2015.

The World Bank and OECD estimate that in 1960, only 42 percent of people in the world could read and write. By 2015 that figure had risen to 86 percent. Some countries – Andorra, Azerbaijan, Cuba, Georgia, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Norway, Poland, Russia, Slovenia and Tajikistan – have literacy rates at or near 100 percent.

However, literacy is a moving target. Many countries now aspire – in accordance with the aims laid out in Article 26 – to make secondary education free and universal, and some aim for more widespread tertiary education. “Literacy” is also being expanded in many places to include the ability to use numbers, images and computers as well as language, and to encompass other ways of communicating and gaining useful knowledge.

But these positive figures mask the fact that progress has also been very uneven, due largely to inequalities and discrimination, with the right to education continuing to be denied to children from marginalized groups and those living in the worst forms of poverty and deprivation. The most disadvantaged children have continued to be left behind, for example children with disabilities, indigenous children and stateless children – and especially girls who belong to these groups.

Despite the steady rise in literacy rates over the past 50 years, there are still 750 million illiterate adults around the world, most of whom are women. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) provide a key opportunity to ensure that all youth and most adults achieve literacy and numeracy by 2030, with SDG 4 in particular addressing both access to, and quality of, education.

In many places, girls are prevented by social and cultural practices from getting an education. In 43 countries, mainly located in Northern and sub-Saharan Africa and Western and Southern Asia, young women aged 15 to 24 years are still less likely than young men to have basic reading and writing skills.

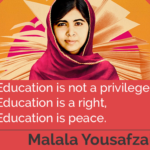

“One book, one pen, one child, and one teacher can change the world.”

– Malala Yousafzai

A lack of education, especially of girls, has been demonstrated to have an enormous impact on society at large, on health, and on the economic development of countries, not least because deprivation of the right to education often spans generations, as it perpetuates entrenched cycles of poverty. Education is perhaps the most powerful tool available to pull marginalized children and adults out of poverty and exclusion, making it possible for them to play an active role in the processes and decisions that affect them.

Education as a fundamental human right is essential for the exercise of all other human rights. It promotes individual freedom and contributes definitively to a child’s broader empowerment, wellbeing and development, not least by ensuring that they are equipped to understand and claim their rights throughout their lives.

Perhaps the most prominent advocate of girls’ education is Malala Yousafzai, a Pakistani activist and the youngest ever winner of a Nobel Prize. When she persisted in attending school in her native Swat Valley after the local Taliban had banned girls from school, Malala and two other girls were shot by a Taliban gunman in an assassination attempt.

Undaunted, she continued to pursue her activities after her recovery. “With guns you can kill terrorists, with education you can kill terrorism,” she says.

Source: United Nations’ Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights

Tags: economic justice, gender justice, immigrant refugee justice, peace education